One fish, two fish: One RI man's mission to count herring and make a difference

The Providence Journal

Tom Mooney | Email Tom Mooney at: tmooney@providencejournal.com

April 15, 2022

WARWICK – From where Paul Earnshaw is standing, shin-deep in turbid water, Buckeye Brook isn’t much to look at.

Shallow and silty, it resembles a drainage trough as it emerges from under four lanes of noisy Warwick Avenue before disappearing downstream beneath brambles and mats of broken reeds.

And yet Earnshaw, 63, is back here streamside for a second time today, back staring into the water where he occasionally pulls out a shopping cart, a place he calls “nirvana.”

“I love this brook.”

The reason could go swimming past his waders at any moment now.

Each April and May, while yellow forsythia and purple azalea trumpet spring's arrival with color, thousands of foot-long, sea-run herring thread their way up into this freshwater stream virtually unseen.

Their spawning migration, out of the ocean and up Narragansett Bay, will take them deep into the suburban sprawl of shopping plazas and housing plats and finally to Warwick Pond, just east of Green Airport, where they hatched about three years ago.

“Something triggers in their system,” says Earnshaw, awe in his voice. “They don’t come back to a random spawning ground, they come back to where they were spawned, which is one of the amazing things that we'll probably never understand about these fish.”

It is early Wednesday afternoon, sunny, with the air temperature 70 degrees. Earnshaw has the day off from repairing home appliances, which is why he is biding his time at the brook.

There are others just like him, volunteers who linger here and at other herring runs along Rhode Island’s coast: at the upper reaches of the Narrow, Sakonnet and Pawcatuck rivers, the Saugatucket in Wakefield, Woonasquatucket in Providence and Ten Mile in East Providence.

Some, like Earnshaw, come to count the herring and hope their numbers rebound. Others, like the more than 100 volunteers who flock like gulls around the herring run in Wakefield, are there to literally give the fish a lift, to net them where they stack up in the current and hoist them over impediments that block their way.

Paul Earnshaw of the Buckeye Brook Coalition wades in Buckeye Brok in Warwick, cleaning off a pair of white boards that volunteers use as a backdrop to more easily count herring on their way upstram to spawn - Kris Craig/Providence Journal - April 15, 2022

These fish need all the help they can get.

River herring are a mix of alewives and blueback herring. They live most of their lives in the ocean, where they mingle with their cousins the Atlantic herring, and consequently get scooped up in commercial nets.

They are preyed upon by just about everything bigger than them, from whales to striped bass. And for hundreds of years now, their spawning migrations have been stymied by the dams of the Industrial Revolution.

But spurred on by the passions of conservation groups, the government and various agencies have spent millions of dollars in recent years to remove dams and erect fish ladders that actually work for herring. In 2006, Rhode Island also joined other states in banning the taking of river herring

The combined efforts have had some modest success, says Patrick McGee, principal freshwater biologist with the state Department of Environmental Management.

At Buckey Brook, tens of thousands of herring show up each year, with the runs of the last two years approaching 100,000, says McGee. The adult fish will stay in the brook for only about two weeks before returning to the sea.

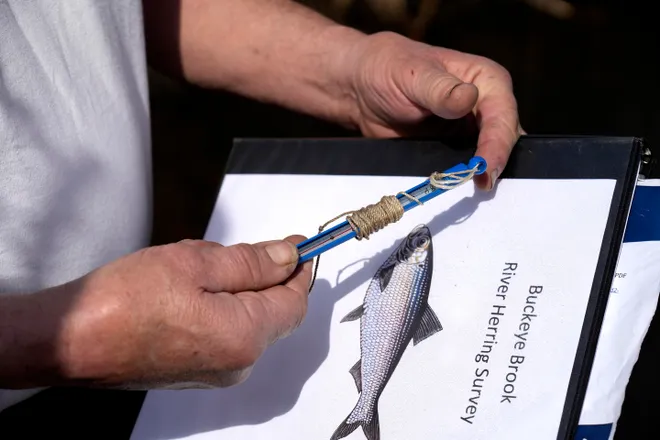

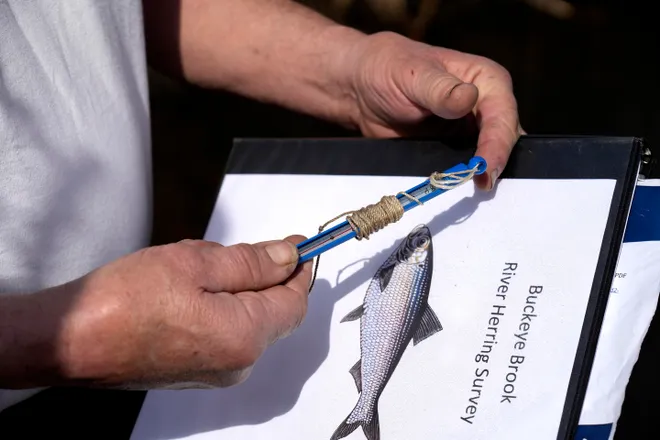

Standing in the brook, Earnshaw uses a pad attached to a long pole to wipe the silt off two white boards secured to the bottom. The boards make it easier to see any fish moving by.

Earnshaw, who is vice president of the Buckeye Brook Coalition, hasn’t seen a fish yet this season, but there are about 9 other volunteers who count herring here whenever they can swing by. They put their tabulations in a book kept in a locked box by the brook.

Earnshaw with a water thermometer and log book for fish counting in Buckeye Brook - Kris Craig/The Providence Journal - April 15, 2022

The counting is done in 10-minute intervals. From their reports, the run is just starting: one volunteer, Bill Hahn, reported seeing seven fish over three 10-minute periods on April 8. Roger Hudson counted 99 fish the next day at 5:20 a.m.; a half-hour later David Woisard counted 103, and after him, Bill Aldrich reported 128 herring swimming over the white boards.

“When there’s a good swarm of fish coming, you’ll see a wake building,” Earnshaw says. “And when you see the wake you just get ready, and that’s when I get this out.”

He removes from the lock box a hand-held counter and gives it a few clicks with his thumb.

Earnshaw grew up a couple of miles from here on Bend Road. His father took him to the brook as a boy to net herring to use as striper bait.

“I would put my net in the water back then and easily harvest 50 fish within 10 minutes,” he says. “It was an adrenaline rush for me as a child. I remember it to this day.”

Earnshaw is himself a fisherman, and in keeping with tradition he took his twin daughters Emily and Susan to the brook when they were about 10. This was before the moratorium on taking herring.

"This is really about the love of nature we all have. We don't want the environment to be lost - to be only a memory of our past"

“I wanted them to experience something as a child I experienced growing up. I wanted them to know what it felt like to put that net in the water and shout ‘Whoa Daddy, I think I got one!’” He mimics holding a net, heavy with flopping herring.

He’s not interested in taking the fish anymore. He just wants to see this spectacle of nature continue.

“This is really about the love of nature we all have,” he says, speaking about the herring volunteers. “We don’t want the environment to be lost – to be only a memory of our past.”

Earnshaw is expecting to be back streamside Saturday morning. There's a full moon this weekend, and he believes the higher tides will push a slug of buckeyes – the colloquial name of the fish – into Buckeye Brook before the sun gets too high.

He wants to be standing right here when they swim by – and greet them as he always does.

“Oh yeah, I’ll shout at them,” he says. “It’s like: ‘Welcome home Buckeye! Come on! Come on!'”